Sweden's Special Schools

Alison McLauchlin and Kathleen Tripp, School of Education and Law

Alison McLauchlin Associate Director in Academic Quality and parent of children with SEND

Kathleen Tripp is a Senior Lecturer in SEND and Inclusion on the BA (Hons) Education Programme

Keywords: Special Schools, Sweden, Comparative Education

Download: Sweden's Special Schools

Following a visit to UH from the staff at Nytida Kung Saga Gymnasium Special School, Stockholm we were invited in May 2023 to explore SEND provision in Sweden. We were given the opportunity to visit Kung Saga, a secondary school for young people with Special Needs and Disabilities (SEND) as well as Nytorpsskolan School, a school for young people with more specific learning differences but without learning difficulties. We would like to share our reflections in this thought piece on our experience and have selected key aspects, in the section on Reflections, that we would like you to consider with us. Before this, we provide some brief contextual information.

Context

The Special Education system in Sweden includes a range of services and schools to ensure compulsory and high-quality education for disabled students in accordance with the Swedish Education Act. (SPSMa, 2023) There are many parallels in recent education policy between the UK and Sweden, both having been driven by a neo-liberal agenda since the 1990s. Parent choice and competition contributed to a market-led economy in education since the 1990s in Sweden and are intended to drive standards along with privatisation of part of the education “market.” If you have been an educator around since the 1990s in the United Kingdom, this may sound familiar already. Parent choice, OFSTED, and a devolution of budgets to schools are similar tools that were used in the UK to drive “competition” and therefore school improvement in the UK (Ball, 2021). In Sweden this has meant the expansion of the private sector with special schools allowed to expand as a “specialised” part of the market (Tah, 2019).

This has resulted in a widening of the range of private special schools, especially for those with Intellectual Difficulties (the Swedish term) and specifically for those with neurological differences such as autism and Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in Sweden (Hjörne, 2016; Tah, 2019). However, critics have pointed out that this has also resulted in heightened segregation in Sweden, a problematic issue for some in the schools we visited (Tah, 2019). There is a tension between the traditional inclusive egalitarian tradition of “one school for all” in Sweden and the increase in segregation of students in special schools due to their special educational needs (Hjörne, 2016).

Kung Saga and Nytorpsskolan School are part of the Nytida company’s group of private special schools that have developed in this context (AMBEA, 2023).

Reflections

Individualisation

In Sweden, the arts as a curriculum priority is driven nationally as it is considered an evidence-based pedagogical approach specifically for teaching students with Special Educational Needs (Sjöqvist et. al, 2021). Arts education is considered a way of developing a range of cognitive, communicative and social skills for children with learning difficulties and is prioritised in the curriculum for children and young people with SEND. Furthermore, principals prioritise specialised arts knowledge over special education knowledge for teachers (Sjöqvist et. al, 2021). Kung Saga conforms to this pedagogical approach in that it focuses on learning through the arts. This allows students to explore their individual interests and talents through a variety of art media with teachers that specialise in music, visual arts, etc.

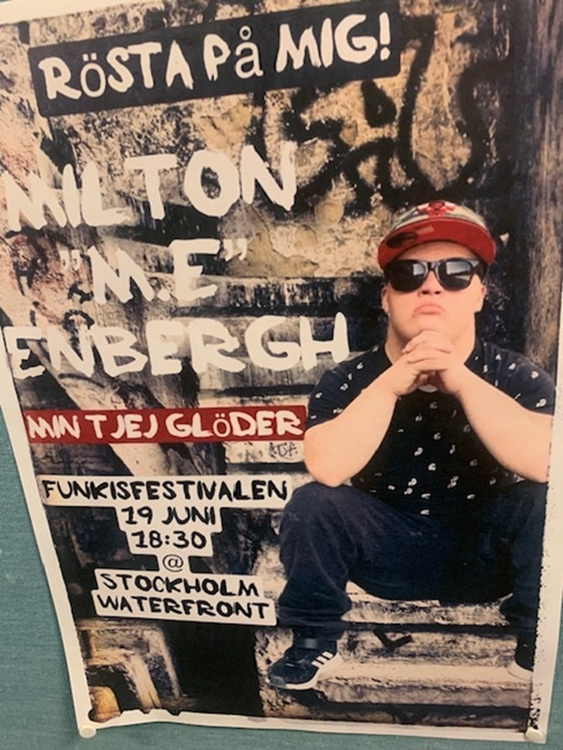

The school performs elaborate shows with music, acting, lights, costumes, and beautiful sets. There is a professional music studio where students can practice and produce their own music. One student will be performing in the youth version of Sweden’s Got Talent. They have even released a powerful music video demanding their rights for education (see image 1).

Image 1 – One student at Kung Saga performed at a festival

The school used a range of familiar approaches; Widget visual supports and schedules, high staff to student ratio, and an individualised approach to the curriculum. The extent of this individualised approach was impressive, as was the use of a games based and reflective meta-cognitive approach that emphasized autonomy and practical skills. One particularly vulnerable student works independently and creates an entire imaginary world of his own making, with elaborate drawings and characters that he develops in a personalised low arousal environment.

Autonomy

Students are strikingly autonomous and students were allowed to have their mobile phones at all times, including using them to play a practical social skills game on answering the phone. They used Google translate to communicate as well as play beats to rap to for spontaneous performances for us. One student has over 35,000 followers on TikTok, he shares his raps and thoughts with a (thankfully) majority of positive support (Image 2).

We were surprised that some students at Kung Saga travelled independently on public transport, and there was a discussion for some other students to begin to travel independently that we would consider “highly vulnerable” and would not be allowed to travel independently in the UK. At Nytorpsskolan School, students were allowed to go out and walk around the neighbourhood independently as a break.

There were two students that had been dating for quite a while and considered each other boyfriend and girlfriend, they were openly physically affectionate and staff celebrated this relationship. Relationships between staff and students as well as staff with each other exhibited a deeply warm, relaxed and caring community, truly a joy to be around.

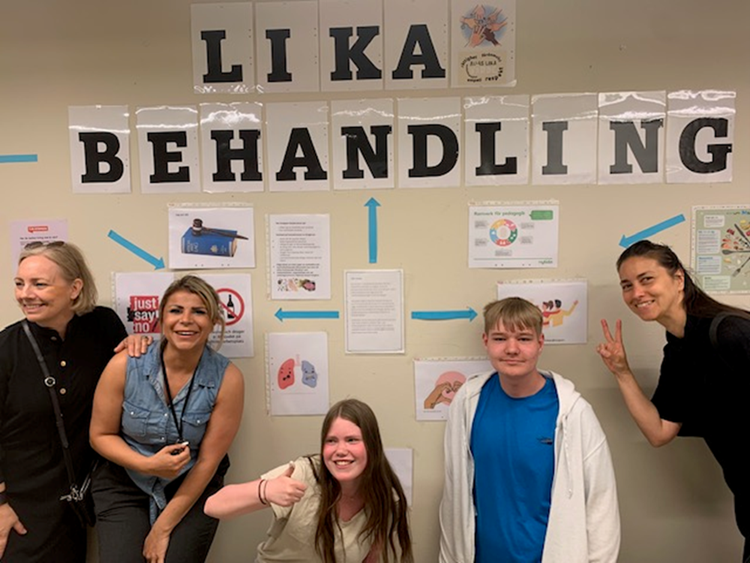

Image 2 – This student has over 35,000 followers on TikTok

Co-operation

We joined the afternoon session where the oldest class had prepared co-operative games for the younger students (Image 3). The particularly interesting aspect of this was not only had the older students prepared the lesson, but they then had a reflection session on how it had gone using the whiteboard and Widget to formulate their reflections.

Image 3 – Musical chairs with Dancing Queen by ABBA

Pedagogical Approach for Academic Success

We also visited Nytorpsskolan school, a special school in Stockholm county that supports students with disability such as ADHD and autism but generally students do not have learning difficulties. Many take exams, and the work displayed looked at a comparable level to a mainstream school. The use of a digital platform provided videos and materials that were highly engaging, explicit, and fun. The approach was informal, relaxed, and focused on the discussion of emotions and social understanding. Any issue that was causing the least bit of discomfort or disagreement was thoroughly discussed and explained in detail before going on with the lesson. Staff modeled talking through their own feelings in detail with students, explicitly explaining their thought processes and emotional regulation strategies. A few students accompanied us throughout most of the visit; teachers allowed them to opt out of lessons when they requested spending additional time with us. The students who accompanied us discussed how they were able to work and study in a relaxed way at Nystorpsskolan. In previous schools they had not been able to “function” but they were able thrive at Nystorpsskolan school. Their only complaint was that the deputy headteacher had taken the fun out of their secret use of swear words by discussing them openly and taking the “shock value” out of them!

The Environment

Initially I was struck by the impact of each of the different environments in both schools we visited. Each setting, located in office type accommodation in the centre of towns oozed a white, clean and Ikea-like home/office appearance coupled with cushioned sofas. The walls were intentionally plain with each setting containing only one small display area. This low arousal sensory environment appeared to instil an air of calm as advocated by Caldwell (2017) providing a space of visual and auditory tranquillity alongside a warm relaxed and friendly atmosphere. It also seemed to facilitate a sense of the focus being on the people inside the building rather than the décor itself.

Image 4 – Typical school environment at Nytorpsskolan school

Behaviour and Relationships

The atmosphere in each of the settings seemed to focus on building and maintaining positive relationships whilst retaining a sense of learning being fun. The pupils behaved calmly and appeared at ease. There was no evidence of children acting out or challenging behaviour in a way that you might expect to see in a comparative special school setting in the UK. Instead, staff acted as friends and educators rather than friendly educators. According to Pastore and Luder (2021) this prioritisation of teacher-student relationship fosters the development of ‘academic psychological capital’ providing hope, resilience, competence and optimism that enables learning.

The familiar UK home constraints of safeguarding and health and safety were pared back to allow for a relaxed but well-constructed learning to take place. Pupils were allowed to sit on their desks or stand with their back to the teacher if that helped them to feel comfortable in their learning and was not considered disruptive or risky. Staff also encouraged individuals’ activities outside school, following them on social media, and were allowed to take pupils out for a walk if students requested. In addition, we witnessed pupils who were not ready to learn in a lesson who were allowed to leave the classroom area and were provided with someone who they could talk to and only returned when they indicated they were ready. The result of this holistic, person-centred approach was evident in the positive engagement of the pupils in their learning and the success in their achievements.

The relationships between staff as well as between staff and students were striking and close. One teacher at Kung Saga said that the joy of teaching in the school was that every day there was a moment of interacting with each young person on a personal level. We witnessed first-hand the camaraderie inside and outside of school hours. Staff were very social with each other and clearly had close friendship bonds. Staff from Kung Saga and Nytorpsskolan frequently spent time outside of school with colleagues and spoke of their “love” of their colleagues. They also spoke of their ability to disagree with each other and have an open dialogue to ensure the best decisions were made.

Image 5 – Staff and students at Nytorpsskolan school

Mental Health and Wellbeing

The majority of the pupils we met at Nytorpsskolan and Kung Saga were autistic and despite communicating with us in a second language they were, with encouragement, all able to introduce themselves. Those pupils that were more articulate spoke passionately about their work and interests. Some of the pupils unsurprisingly demonstrated low-level anxiety. However, on the basis of these observations and discussions with the staff, it appeared to us that these schools had experienced less than the 50% increase of mental health issues such as reported in the UK (The Children’s Society 2022). If what we observed was common then it may be worth reflecting on the two countries’ approach to the pandemic, a period that has had significant impact in school aged children. In the UK the decision was as a nation to isolate. In contrast the Swedish approach was to develop pack immunity through socialisation. Could it be that these two approaches had differing impacts. In the UK we have seen a significant increase in school aged children reporting issues with their mental health and wellbeing (MHWB) (Asbury et al 2021) and that perhaps social isolation restricted the development of social skills resulting in this a negative impact. Whereas the approach in Sweden helped to maintain socialisation skills, building resilience which perhaps reduced the impact on MHWB.

Questions for Further Thought

One important point that we were struck with was how thought-provoking and invaluable the process of exchanging ideas and understanding with international colleagues is to understanding one’s own education system. Assumptions were challenged as to why we do things in the UK the way we do. Our most striking thoughts were around the following;

- The importance of the arts. What is the pedagogical evidence for using the arts for students with SEND? Is the UK obsession with results-driven prioritisation of Literacy and Maths meeting the needs of students with SEND? Whatever happened to the “Broad and Balanced” curriculum for all students?

- The value of non-hierarchical relationships between staff members as well as between staff and their students. Are flexibility, co-operation, and mutual respect better ways to support behaviour and learning than a reward and sanctions systems?

- The pro and cons of safeguarding and the impact on relationships and autonomy. Have we gone too far with safeguarding procedures and are we stifling positive relationships, problem solving skills, and access to unsupervised environments and is this preparing students for life?

- The sense of equality, belonging and community. The schools we visited are part of buildings that are integrated into community buildings. Have UK schools prioritised independence and league tables over the need for community and respect?

- Calmness in all aspects – the environment and attitude towards inspections, student behaviour. What is the key to this, is the UK education breeding tension and anxiety that impacts pupils?

The key words we came away with were autonomy, community, and joy. For a long time, it was difficult to put into words what was felt and witnessed. We have maintained contact with our Swedish colleagues through a research project with the BA (Hons) Education programme as there was such keen interest to maintain the dialogue and exchange of ideas. We will continue to build on these valued relationships to develop our thoughts further.