Professional learning and development approaches and activities for teacher mentors: ideas from the literature

Elizabeth White and Claire Dickerson

School of Education, University of Hertfordshire

Abstract

Teacher mentors working with student-teachers or early career teachers play a vital role in the preparation of new teachers, and their professional learning and development (PLD) is of increasing interest to policy makers, schools, and providers of initial teacher education. This article provides ideas for those with responsibility for developing programmes of mentor PLD. Drawing on international research literature, it presents and discusses a range of approaches and activities that enable teachers to learn and develop as mentors.

Keywords

professional learning; professional development; teacher mentor; student-teacher; early career teacher.

Funding

This work was funded by an internal grant from the University of Hertfordshire.

Introduction

Teachers who are mentors play a significant part in the development of other teachers, usually at an early stage of their career. In England policy makers have increasingly focused on initial teacher education (ITE) and development for early career teachers (ECTs) (Department for Education, 2011; 2019). More recently, this focus has broadened to include mentor training (Department for Education, 2023). The statutory requirement for accredited ITE providers to train mentors for a minimum of 20 hours initially, with further annual refresher training (Department for Education, 2024a), has been dropped. However providers are required to ‘ensure that all mentors receive sufficient high-quality training to ensure they can effectively support a trainee teacher to obtain the knowledge and skills they need to successfully complete their ITT school placement’ (Department for Education, 2024b). The training for mentors of early career teachers (ECTs) is being delivered on a national scale with a ‘one-size-fits all’ approach leading to concerns that mentor training material is being used inflexibly rather than being adapted to the needs of mentors and experienced teachers (Vare et al., 2022).

This article addresses the current focus on ‘training’ teacher mentors. In summarising some of the PLD approaches and activities reported in the international literature it can provide ITE providers engaged in designing their mentor training curriculum with a breadth of knowledge to inform their practice and develop their understanding of the mentoring research base. The article first explains what is meant by mentor PLD and then describes the literature search and presents and discusses the findings.

Background

Definition of PLD

In this article mentor PLD is defined as learning something that is potentially of value to mentors as professionals, through engaging in formal and informal opportunities leading to mentors developing their professional behaviour, knowledge, skills, attitudes, beliefs, values, identity and/or mission (drawing on the work of Korthagen, 2004).

Informal professional learning and development approaches and activities

Opportunities for mentor PLD can be categorised as informal or formal. Informal opportunities are unintentional and come through the practice of mentoring itself. The literature presents multiple accounts of teachers gaining from the role of mentor, improving their own teaching (Law, 2013; Young and MacPhail, 2015; Bal-Gezegin, Balıkçı and Gümüşok, 2019; Walters, Robinson and Walters, 2020) and collaboratively learning with their student-teachers (Aderibigbe, Colucci-Gray and Gray, 2014; Young and MacPhail, 2015). Mentors can develop as communicators because of the mentoring relationship and gain new teaching skills through mentoring (Hobson et al., 2009). These examples of PLD arising from the practice of mentoring itself are focussed on the mentor learning about teaching alongside their student-teacher, rather than learning about the practice of mentoring. It is likely that ‘the learning of the mentor within the mentoring process is generally involuntary and unplanned’ (Nyanjom, 2020, p. 253). The mentoring journey can provide developmental opportunities to mentors and student-teachers through deliberate creation of a co-learning and collaborative space, with critical reflective practice and inquiry into professional practice (Hobson et al., 2009; Shanks, 2017). Additionally, ‘mentoring relationships may offer the most appropriate training grounds for mentors to investigate their mentor identity and improve their mentoring competencies’ (Nyanjom, 2020, p. 254).

Formal professional learning and development approaches and activities

Formal PLD opportunities for mentors can be provided through courses or education involving universities, other teacher education providers or researchers, or arranged deliberately with peers. These formal opportunities are intentional and planned, although there may be examples where the process is planned to an extent but the expected learning is not identified beforehand, for example, peer/collaborative type activities. From their review of the literature, Hobson et al. (2009) claimed that programmes that entailed professional knowledge, research and skills in mentoring, and enabled mentors to develop their mentoring identities were the most significant in impacting the effectiveness of mentors, rather than programmes that involved simply shadowing and observing experienced mentors.

Research Questions

- What PLD approaches or activities are used / could be used with teacher mentors?

- What skills / attitudes / characteristics / competence can be developed?

For empirical studies:

- What was the effect of the PLD?

- What was the size of the study?

Method

- Group 1: teacher mentor / school-based mentor / cooperating teacher / co-operating teacher

- Group 2: professional learning / professional development / CPD / training

- Group 3: approach / activity

- Group 4: skills / attitudes / characteristics / competence

Each search term from group 1 was combined with each search term from group 2 to give sixteen permutations (for example, “teacher mentor” AND “professional learning”) and the publications identified in each case were screened for use of an “approach or activity” (group 3) designed to develop mentoring skills, attitudes, characteristics, competence (group 4). The Teacher Education Advancement Network (TEAN) Journal was also searched. Articles published in this journal are particularly relevant for teacher educators in the UK.

Publications from 2010 onwards were included in the search because this is when more intensive involvement of schools in ITE partnerships was becoming established and when more students were on school-based routes (Department for Education, 2010, 2011; Mattsson et al., 2012). In many countries the school environment changed considerably in relation to mentoring in ITE from around 2010 so it was thought that resources published before then might be less relevant and transferable. Additional resources identified by the researchers were also included as well as some findings relevant to teacher PLD. A total of 106 relevant texts were retrieved of which 37 were reports of empirical studies, the others being mainly reviews or theoretical papers.

The reports of empirical studies were reviewed for references to the attributes mentors need to develop, and for PLD approaches and activities. The literature analysed for the study mainly focussed on mentors working with student-teachers with only one reference to early career teachers.

Findings

The opportunities discussed below illustrate different formal PLD approaches and activities. There is inevitably some overlap between them.

Mentor professional learning and development approaches and activities

Many of the 37 papers summarised in Table 1 (at end of article) reported feedback from the mentors themselves regarding their learning and their use of new knowledge and skills and it is this feedback that was used to assess the effectiveness of the PLD. Eleven of the papers included feedback from student-teachers and four included feedback from school or university-based teacher educators involved in the ITE programme at partnership level. Where student-teacher feedback was collected, positive outcomes were found for student-teachers who worked with mentors who had received professional development opportunities to prepare them for the mentoring role (van Velzen et al., 2012; Lafferty, 2018; Bal-Gezegin, Balıkçı and Gümüşok, 2019; Rickard and Walsh, 2019; Chaplin and Munn, 2020; Richardson et al., 2020; Wexler, 2020). In one study of effectiveness of mentor PLD, no significant difference was found on ECTs’ outcomes including retention and satisfaction, whether the mentor was supported or not (Hetrick, 2015). However, in this study mentor support included a composite of approaches which could have masked the effectiveness of any particular approach.

Table 2 (at end of article) provides a summary of further mentor PLD approaches or activities identified from eight papers reporting reviews or where empirical research is not directly reported.

Table 3 (at end of article) presents a summary of some PLD approaches or activities used with teachers that could be considered suitable for mentors from four papers where empirical research is not directly reported.

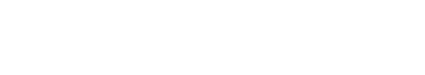

Figure 1 (below) summarises the approaches and activities identified in the literature and how they interrelate. The yellow boxes contain lists of approaches and activities that may be used independently of a programme, workshop or formal Professional Learning Community (PLC). These approaches and activities are discussed in the remaining sections of the article.

Programmes

The main form of mentor PLD reported in the literature reviewed here involved specifically developed programmes, of varying lengths, from two days to three years (Koballa et al., 2010; Hudson, 2013; Ambrosetti, 2014; Aspfors and Fransson, 2015; Beutel et al., 2017; Daly and Milton, 2017; Navrátilová, 2017; Robinson and Hobson, 2017; Gardiner and Weisling, 2018; Grimmett et al., 2018; Lafferty, 2018; Thomsen, 2018; Perry and Boodt, 2019; Richardson et al., 2020; Uworwabayeho et al., 2020; Walters, Robinson and Walters, 2020; Wexler, 2020; Yılmaz and Bıkmaz, 2021). In many cases the programme ran alongside the experience of mentoring, allowing direct application of professional learning into practice (Richardson et al., 2020; Uworwabayeho et al., 2020; Wexler, 2020).

Some mentor PLD programmes focussed on using a particular approach such as reflection (Lafferty, 2018); collaborative inquiry (Beutel et al., 2017); instructional coaching (Richardson et al., 2020); and educative mentoring (Gardiner and Weisling, 2018; Uworwabayeho et al., 2020; Wexler, 2020). Stanulis et al. (2019) describe the use of six mentor study groups focussed on enacting educative mentoring, which might also be described as a mentor PLD programme. Twoli (2011) describes mentoring modules on a master’s programme, which could also be recognised as a mentor PLD programme. Other programmes were used alongside additional opportunities for PLD, for example, ‘mentoring the mentor’ and ‘peer mentor shadowing’ (Gardiner and Weisling, 2018; Thomsen, 2018); and developing a professional learning community (PLC) (Perry and Boodt, 2019).

In England the original requirement for mentors to have initial training of a minimum of 20 hours, depending on their prior learning, has raised the profile of programmes, focusing on developing a professional network of well-trained and expert mentors who understand the ITE curriculum (Department for Education, 2024a). A caution with programmes is that they can be imposed inflexibly, in a top-down manner, whilst the need is for contextualised, collaborative opportunities that are personalised for the diverse needs of those developing as mentors (Betlem, Clary and Jones, 2019). However, collaborative opportunities can be time-consuming, so tight structures are required.

Workshops

Rickard and Walsh (2019) describe using two mentor PLD workshops to support learning about team teaching, and Wallis (2012) describes the use of two workshops to develop skills for observing and giving constructive teaching to support the teaching of language in primary settings. Although shorter than mentor PLD programmes, these opportunities are comparable to the focussed programmes above, with university-based teacher educators collaborating with mentors to develop their practice.

Professional Learning Communities

Mentors may learn through being part of a PLC, alongside other mentors, university-based teacher educators and/or student-teachers (Gallo-Fox, 2010; Nielsen et al., 2010; Young and MacPhail, 2016; Holland, 2018; Betlem, Clary and Jones, 2019; Perry and Boodt, 2019; Chaplin and Munn, 2020). In most of these reports the PLC is occurring through what also may be seen as a mentor PLD programme. Additionally, mentor PLD programmes can offer the opportunity to build a PLC for mentors. Hence the distinction between these opportunities is blurred.

Whilst a PLC may be within a community of practice, alongside other teacher educators, the learning may not be through ‘legitimate peripheral participation’ (Lave and Wenger, 1991, p. 25) where newcomers are given legitimacy to learn by participating on the edge of a community of practice, because mentors are fully responsible for their student-teachers’ learning from their first day as a mentor (Young and MacPhail, 2015). Additionally, where there is only a single mentor and student-teacher pairing, the mentor is not necessarily experiencing a community of practice alongside other mentors and university-based teacher educators. In these cases (Gallo-Fox, 2010; Young and MacPhail, 2016) a mutual professional learning relationship might be a better description.

Chaplin and Munn (2020) report target setting and assessment skills being generated through PLCs, whilst Nielsen et al. (2010) found that inquiry into practice in a PLC produced new ways of working with student-teachers. Perry and Boodt (2019) discovered that within a PLC, reflection on practice led to the development of confidence and practice as mentors.

Denis (2017, p. 54) focusses on ‘A Triumvirate Approach’ of student-teacher, mentor and university-based teacher educator providing planned opportunities for reflection and development of mentoring practice, including video conferencing, asynchronous preparation videos and case studies around specific issues. This seems to be a form of PLC.

The PLC depicted by Gallo-Fox (2010) was between the mentor and their student-teacher. Co-teaching provided opportunities for risk-taking within a supportive environment. Mentors expanded their pedagogical repertoire through regular experimentation with new ways of teaching. This example correlates better with those where PLD comes through the practice of mentoring itself, being focussed on the mentor learning about teaching alongside their student-teacher, rather than intentionally learning about mentoring.

Impedovo (2021) described epistemic collaborative communities through an online social network. Whilst this research was around teaching rather than mentoring, the network provided a space for teachers to examine challenges in practice, identify and evaluate solutions, share ideas and resources, exchange knowledge and build collective meaning about experiences in practice. This would be equally applicable to developing mentoring practice and could be described as an online PLC. Helleve (2010) describes online PLCs using action research and reflection between teachers and university-based teacher educators. This too could be helpful for mentor development. Action research in a PLC is also described by Betlem, Clary and Jones (2019), and was found to positively impact mentoring practice.

A further example of a PLC using online provision is the professional learning website of Project Evidence, which contains five learning modules that student-teachers, mentors and university-based teacher educators can learn collaboratively from (Allen, White and Sim, 2017). This moves the focus of the mentor onto their own professional learning, rather than on supervising and assessing student-teachers. Nielsen et al. (2010) stress the importance of reducing hierarchical structures to enable PLCs to develop.

Narrative

Narrative-based resources can be used collaboratively for mentor PLD, to provide new insights and understandings about practice and working in partnerships to support student-teachers (Smith, 2012; White, Timmermans and Dickerson, 2020a, 2020b; White, 2021). They have the advantage of effectively communicating complex issues and dilemmas of practice and allowing personal values to be considered. Koballa et al. (2010) used case studies of dilemmas in practice during their mentor PLD programme, which is a similar approach.

Action research

Action research can be a useful approach for mentors to develop their mentoring practice through fostering a culture of collaborative inquiry (Helleve, 2010; Betlem, Clary and Jones, 2019), or self-study (Nyanjom, 2020). Action research is one of several approaches for enhancing reflection and expanding new dimensions of knowledge during the mentoring process (Aspfors and Fransson, 2015).

Formative support materials

Carroll, McAdam and McCulloch (2012) report on the provision of professional knowledge spaces by developing resources for use by mentors, to enable inquiry into practice and structured conversations with student-teachers. Collaboration was supported by asynchronous three-way learning conversations between the university-based teacher educator, mentor and student-teacher. These resources can be provided online, and may be interactive (Schaefer, 2021; White, Mackintosh and Dickerson, 2022). They could be used independently or may be a useful way to supplement synchronous, in person or remote, mentor PLD.

Coaching mentors, ‘mentoring the mentor’ and shadowing mentors

Coaching mentors, mentoring mentors and shadowing mentors are PLD opportunities that can exist in the school setting (Gardiner and Weisling, 2018; Thomsen, 2018; Keiler, Diotti and Hudon, 2020; White, Mackintosh and Dickerson, 2022). More experienced colleagues who coach or mentor mentors may come from within the school or from outside. This can provide a way for mentors to receive one-to-one support and personalised PLD. Coaching can be used to develop specific skills like giving feedback (Keiler, Diotti and Hudon, 2020), whilst mentoring usually is more general and takes place over a longer time. Peer mentor shadowing has been found to strengthen the self-efficacy of mentors (Thomsen, 2018). These forms of PLD might be particularly helpful when used alongside one or more of the other opportunities for mentor PLD.

Grassroots opportunities

The term ‘grassroots professional development’ (Taylor, 1998, p. 347) or grassroots PLD is used when teachers instigate their own PLCs to develop their practice (Holme, Schofield and Lakin, 2020). This is possible for mentor PLD. Although not reported in this selection of literature, grassroots mentor PLD might be occurring locally, created by mentors who want to develop their mentoring practice alongside peers and have an intent to learn while mentoring. The School Advisor Network of the University of British Columbia, Canada, described by Clarke et al. (2012) is a similar form of PLD, formed in response to a desire for space for an on-going and meaningful conversation about mentoring. Members of this research group of mentors were actively inquiring into their practice and taking greater responsibility for their PLD. A university project team was committed to supporting the mentors in the activities and inquiries they wished to undertake.

Intervision

Intervision is where peer groups of mentors problem-solve collaboratively, providing mutual counselling and developmental support, finding their own solutions and strategies to cope with challenges in practice through systematic experience sharing (Franzenburg, 2019). Although this could happen as a form of grassroots PLD, it seems more likely that intervision groups would be arranged by a teacher educator from a school, university or other provider, supervising a group of mentors.

Educative mentoring practices

Mackintosh (2019) has suggested that the key practices of educative mentoring are situated inquiry into practice; joint work between the student-teacher and mentor; foregrounding the learning of pupils; articulating the reasoning behind teaching and having two foci - the long-term goals and the short-term concerns of the student-teacher. Whilst these practices help both mentor and student-teacher to develop their teaching (Polombo and Daly, 2022), they can also help mentors to develop their mentoring practices when given the opportunity to reflect on their mentoring in a PLC (Pylman, 2016; Gardiner and Weisling, 2018; Stanulis et al., 2019; Uworwabayeho et al., 2020; Wexler, 2020).

Co-teaching, co-planning, analysing pupil work, lesson study, lesson observation and feedback are high-leverage practices in educative mentoring. Co-teaching has been found to expand the teaching practice of mentors, as well as their student-teachers, through reflection on practice (Gallo-Fox and Scantlebury, 2016). van Velzen et al. (2012) reported that their collaborative mentoring approach, using collaborative lesson planning, enactment, and evaluation, was effective in developing deeper conversations than in regular mentoring conversations, so that the reflection on practice was also developing the quality of the mentoring taking place. Pylman (2016) describes intentional educative co-planning, using video recording of the mentor-student-teacher conversation to aid reflection on practice, finding it supported mentor development. Marsh and Mitchell (2014) also used video, recording the student-teacher’s lesson to aid the feedback dialogue, and to support the link between theory and practice. This could also be a helpful tool for mentor PLD, especially when used collaboratively with a peer or a university-based teacher educator. When mentors and student-teachers carry out lesson study, there is an impact on the teaching of mentors (Cajkler and Wood, 2016). Lesson study can also deepen dialogue between the mentor and student-teacher, reflecting on practice in relationship to the learning of specific pupils, again with potential for developing the quality of mentoring. Traditionally, some mentors might have focussed on giving psychological support and technical advice to support entry into the profession, through observation and assessment of the student-teacher and transmitting ‘what we do here’. Educative mentoring is an alternative approach, which involves collaborative dialogue, where the mentor is a critical friend, learning alongside the student-teacher. The dialogue is focussed on pupil learning and the classroom becomes a site of inquiry into practice. Educative mentoring develops the professional knowledge and understanding of both the mentor and the student-teacher through social constructivism.

Instructional coaching

Instructional coaching can be used by mentors with their student-teacher to analyse practice, set targets, explain the rationale for teaching strategies and to provide support to meet those targets. Having a specific target over a short time frame supports student-teachers to achieve and progress. This practice is distinguished by reiteration of the same specific skills several times, providing focussed feedback that specifies what and how the student-teacher needs to improve (Sims, 2019). Software tools and other resources are available to support mentors in deconstructing and articulating their practice. Instructional coaching can also be a high-leverage practice in educative mentoring when it is used fully in the constructivist way that was originally intended (Knight and van Nieuwerburgh, 2012; Lofthouse, 2022; White, Mackintosh and Dickerson, 2022). However, care needs to be taken to avoid a mechanistic approach and to appreciate the term ‘instruction’ in the American way - as teaching rather than as a directive command. Misunderstanding this term can be detrimental to the desired supportive and dialogical relationship of the mentor and their student-teacher (Lofthouse, 2022). Richardson et al. (2020) found that through a strong mentoring relationship, reflecting on practice together and using instructional coaching led to a perceived satisfaction with the quality of relationship between the student-teacher and mentor.

Conclusion

A variety of approaches or activities that can enable teachers to learn and develop as mentors are reported in the literature and are summarised in Tables 1-3 and Figure 1. These examples provide a rich bank of ideas for practitioners and policymakers in the field. In designing formal PLD opportunities for mentors, consideration needs to be given to aligning the activity or approach to the purpose of the PLD. It is imperative to consider more than acquiring and improving mentoring skills that focus on developing student-teachers, but also to include a focus on the personal and professional development of the mentors themselves. Programmes, workshops and PLCs can all have their place, and within these different PLD opportunities narrative, action research, intervision and formal support materials can be beneficial. Coaching and mentoring mentors can supplement programmes. Grassroots opportunities for mentor PLD may also arise, and providing examples of these may prove inspirational to teachers who have a passion to develop as mentors. Finally, educative mentoring can enhance both the work of mentors and support their own PLD when supplemented with opportunities for reflection within a PLC.

Table 1: Summary of empirical articles on mentor professional learning and development

| Opportunities for PLD | Effectiveness (what has changed i.e. where has it had an effect) | Country | No. of participants | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asynchronous online mentor PLD | Shift in understanding of role. Online content incorporated within their mentoring work. Feedback used to adjust practices. | USA | 14 mentors | Schaefer, 2021 | |

| Three-day mentor PLD programme | Looked at learning needs rather than effectiveness of mentor education programme. | Turkey | 13 university-based teacher educators, 20 mentors, 238 student-teachers | Yılmaz and Bıkmaz, 2021 | |

| Professional learning community of mentors, university-based teacher educators and student-teachers | and assessment. | England | Mentors and student-teachers (number not stated) | Early Years Teachers | Chaplin and Munn, 2020 |

| Mentor PLD programme for using instructional coaching alongside using it in school | Development of strong dyad relationships to reflect on practice (as perceived by mentors and student-teachers); development of mentoring skills despite having differing personalities and styles; focus of school culture on pupil achievement as impetus for lesson planning. | USA | 119 mentors | Richardson et al., 2020 | |

| The process of mentoring itself | Professional growth with respect to their own teaching identity and teaching practice. | Canada | 2 mentors | Walters, Robinson and Walters, 2020 | |

| Mentor PLD programme for educative mentoring (alongside mentoring in school) | Reflection on practice, implementation of different teaching ideas, and introduction to new/emerging theories. Continuous learning and growing. | USA | 1 mentor/ student-teacher pair | Wexler, 2020 | |

| Mentors using their mentoring practice as focus for action research in professional learning groups | Shift in mentoring practice. | Australia | 12 mentors | Mentors in three groups | Betlem, Clary and Jones, 2019 |

| The process of mentoring itself | Personal and professional growth. Personally: feeling updated, refreshed motivated and enthusiastic, being more productive, self-reflection opportunities. Professionally: developing, adapting new materials, updating tests and using new techniques. | Turkey | 2 mentor/ student-teacher pairs | English as a Foreign Language teaching | Bal-Gezegin, Balıkçı and Gümüşok, 2019 |

| Two mentor PLD workshops to team teach | Resources, ideas and teaching methods shared. | Ireland | 15 mentor/ student-teacher pairs | Rickard and Walsh, 2019 | |

| Learning through developing as an educative mentor in mentoring study groups | Increased ability to co-plan, observe and debrief and analyse pupil work with student-teacher in educative way. | USA | 10 mentors | Stanulis et al., 2019 | |

| 40 hours mentor PLD programme as an educative mentor, one-to-one's (mentoring the mentor) and shadowing | Understanding of role shifted across the year from mentor-as-expert or transmission orientation to more collaborative debriefs fostering new teachers’ active problem solving, thinking and decision making. | USA | 9 mentors | Gardiner and Weisling, 2018 | |

| Mentor PLD programme (called Teacher Academies of Professional Practice, TAPP) | Shift in how they understood and enacted their roles. Some also underwent shifts in their sense of themselves as professional educators, as evident in their enhanced confidence as teachers, and reconceptualisations of their relationships and positioning with university-based personnel. | Australia | 5 mentors | Grimmett, Williams and White, 2018 | |

| Mentoring community of practice (through 4 workshops using participatory action learning action research strategy) | Participants reported that engaging in and with a mentoring community of practice was effective PLD beneficial for them as developing mentors. | Ireland | 12 mentors | Holland, 2018 | |

| Mentor PLD programme, especially with a focus on supporting reflection | Greater enactment of practices overall and in particular practices related to prompting reflection, goal setting, providing feedback and demonstrating teaching strategies. Associated with a high-quality field experience for student-teachers. | USA | 146 mentors and 119 student-teachers | Lafferty, 2018 | |

| Three-year mentor PLD programme and peer mentor shadowing | Programme led to greater self-efficacy for their roles. Peer mentor shadowing opportunities found to be of the greatest impact leading to stronger self-efficacy. | USA | 5 mentors | Thomsen, 2018 | |

| Mentor PLD programme (called Mentoring Beginning Teachers, MBT) | Building a common language and shared understanding around the role of mentor, consolidating a collaborative inquiry approach to mentoring and providing opportunity for self-reflection and critique around mentoring approaches and practices. Greater self-awareness and validation of mentors’ own teaching performance. | Australia | 17 mentors | Beutel et al., 2017 | |

| Mentor PLD programme | Reconceptualisation of mentoring. | Wales | 70 mentors | External mentors | Daly and Milton, 2017 |

| Mentor PLD programme | More understanding of self and ability to deal with conflict. | Czech Republic | 10 mentors | Navrátilová, 2017 | |

| Accredited and non-accredited mentor PLD programmes | Awareness of requirements of the role and different approaches to mentoring; reflection on and improvement of mentoring practice. Deeper insights into mentoring practices, including how to: provide feedback to mentees; provide guidance to mentees to support their development of professional standards; share good practice; and adopt an appropriate style and pace to mentoring. | England | 20 mentors | FE teaching | Robinson and Hobson, 2017 |

| Co-teaching | Renewed energy toward their practice. Expanded classroom curriculum and practice. Reflection on practice promoted personal growth. Developed as teacher educators and leaders. | USA | 8 mentors | Gallo-Fox and Scantlebury, 2016 | |

| Co-planning | Developing as an educative mentor. | USA | 1 mentor | Pylman, 2016 | |

| Professional learning community of mentor with student-teacher | Mutual engagement, joint enterprise and a shared repertoire of mentor and student-teacher. | Ireland | 18 mentors | Young and MacPhail, 2016 | |

| Lesson study | Impact on their own teaching and understanding of learners; development of pedagogical skills. | England | 9 mentors, 12 student-teachers | Cajkler and Wood, 2016 | |

| Mentoring as a collaborative learning journey using critical constructivist approach | Strengthened collaborative learning between mentor and student-teacher. | Not specified | 6 university tutors, 6 mentors and 7 student-teachers | Aderibigbe, Colucci-Gray and Gray, 2014 | |

| Mentor PLD programme to develop knowledge about the nature and process of mentoring, and the roles of mentors and mentees | Improved quality experience for pre-service teachers during a professional placement because of enhanced confidence of mentors. | Australia | 11 mentors | Ambrosetti, 2014 | |

| Two-day mentor PLD programme and then the process of mentoring itself | Enhanced communication skills, developed problem-solving, leadership building capacity and advanced pedagogical knowledge. Improved quality mentoring of preservice teachers through explicit mentoring practices, and mentors' pedagogical advancement through reflecting and deconstructing teaching practices. | Australia | 101 mentors | Hudson, 2013 | |

| The process of mentoring itself | Developed reflection, articulation of teaching practices, collaboration and shared problem solving, new ideas/strategies, meaningful conversations. | Canada | 13 mentors | Law, 2013 | |

| Provision of professional knowledge spaces by developing formative support materials to be used by mentors to support student-teachers through the use of structured conversations and a process of inquiry into practice. | Indications of increased efficacy of mentoring practice. | Scotland | 120 student-teachers | Carroll, McAdam and McCulloch, 2012 | |

| Collaborative narrative-based PLD | New insights and understandings about the complex nature of supporting colleagues new to the profession. | Canada | 12 mentors and 12 student-teachers | Smith, 2012 | |

| Collaborative mentoring approach using co-planning; co-teaching; lesson evaluation | Increased awareness of behaviour and practical knowledge, and language to discuss behaviour and ideas. | Netherlands | 3 mentor/ student-teacher pairs and 2 school-based teacher educators | van Velzen et al., 2012 | |

| Two workshops developing the skills required to observe and give constructive feedback with mentors and university-based teacher educators learning together | Extended understanding of teaching primary language. Increased skills as teachers. | England | 6 mentors and 8 student-teachers | primary language lessons | Wallis, 2012 |

| Co-teaching professional learning community | Expanded pedagogical repertoire. | USA | Not accessed | Gallo-Fox, 2010 | |

| Mentor PLD programme 50-hour course; a year of support as they mentored; presentation at end of year. Used case studies of dilemmas in practice | Felt better prepared to navigate challenges within their schools, advocate for change, and help novice science teachers to do the same. | USA | 37 | specific to science teaching | Koballa et al., 2010 |

| Professional learning community of mentors and university‐based teacher educators. Monthly group meetings of this inquiry community over two school years | Generated new ways to think about the practicum and about their work with student-teachers. | Canada | 4 university-based teacher educators, 21 mentors | Nielsen et al., 2010 | |

| Mentor PLD programme for educational mentoring with a professional learning community alongside mentoring in school* | Changed practices and behaviour. Learnings from the programme translate into changes in practices. | Rwanda | 300 mentors | Uworwabayeho et al., 2020 | |

| Coaching the mentor on feedback skills (in practice)* | Changed mentoring practice (not specific – explored experiences and perspectives of the mentors). | USA | 25 mentors | specific to science teaching | Keiler, Diotti and Hudon, 2020 |

| Mentor PLD programme and a professional learning community* | Reflecting on and developing practice. Increased confidence. | England | 34 mentors | FE teaching | Perry and Boodt, 2019 |

*Mentor PLD – not specific to ITE or ECTs

Table 2: Summary of other articles on mentor professional learning and development

| Mentor PLD approach or activity | Specific strategies | Essential skills being developed/impact | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Educative mentoring | Use of classroom as site of inquiry. | Professional knowledge and practice through shared, critical thinking about how to respond to learners’ needs and the demands of learning in the subject. | Linked to a vision of good teaching and a developmental view of learning to teach, rather than mentoring approaches linked to psychological support and technical advice. Approach can support the career-long development of teachers. | Polombo and Daly, 2022 |

| Collaborative narrative based PLD | Use of narratives of dilemmas in practice. | Partnership working; guidance of student-teachers; assessment of student-teachers; professionalism; wellbeing; quality assurance. | Can be used in workshops or as part of a mentor PLD programme. | White, 2021 |

| Learning through educative mentoring practices | Instructional coaching, co-planning, co-teaching; lesson study observing and giving feedback; and analysing pupil work. | Mentoring practice as joint work, situated inquiry, articulating the reasoning behind practice, focusing on pupil learning and addressing the long-term goals of student-teachers as well as short-term concerns. | This is a conceptual stance toward mentoring. | Mackintosh, 2019 |

| Active and consistent mentor preparation using a triumvirate approach | Intentional opportunities to interact and reflect on teaching and learning. Multiple activities allow to adapt to experience and beliefs among mentors. University staff investing in time to build relationships with mentors. | Personal relationships, expectations, reflective practice and power structure | Opportunities could include video conferencing sessions or preparation videos, to offset attendance problems; mentors and student teachers examining case studies to consider how each would address a situation. | Denis, 2017 |

| Mentor informal learning and interactions with student-teachers and formal PLD | a) Formal courses or education involving universities, teacher education institutions or researchers; b) Professional development activities, such as coaching or reflective seminars for mentors; c) Action research projects involving mentors and researchers. | Mentors' understanding of teaching and mentoring. | Meta-synthesis of 10 research articles on mentor education which stresses the importance of a systematic, long-term and research-informed mentor education. | Aspfors and Fransson, 2015 |

| Use of video for feedback on lessons (asynchronous) | A tool for mentors to use to support student-teacher development. | Dialogue between theory and practice. | May also provide helpful tool for mentor PLD especially for mentoring the mentor. | Marsh and Mitchell, 2014 |

| Two years at master’s level in Education including mentoring units | Emphasis on mentoring process techniques and skills used during the course and thereafter. | Experience, confidence, and skills in mentoring. | A move towards mentor PLD in Kenyan context. | Twoli, 2011 |

| Project evidence: development of a professional learning website with 5 learning modules | Uses a “laboratory” model where student-teachers reflect beyond the technical skills of teaching to consider the moral and ethical issues involved in teaching and learning in a particular social context. This is extended using a community of practice approach. | Professional knowledge of initial teacher education. | In Australian context - repositions the emphasis of the work of the mentor away from the dual role of assessor and supervisor to encompass their own professional learning. Provides a hybrid space for student-teachers, mentors and university-based teacher educators to learn alongside each other. | Allen, White and Sim, 2017 |

Table 3: Summary of some teacher professional learning and development approaches and activities that could be considered for mentors

| PLD approach or activity | Specific strategies | Essential skills being developed | Comments | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Epistemic Collaborative Communities | Social Networks (a Digital Networked Community of Practice) | Teachers sharing and building collective meaning about their own teaching experiences to increase quality in education. Sharing resources and ideas and facilitating knowledge exchange. | Social networks can be considered as “third spaces” between formal and informal learning to support PLD, also integrating international and intercultural aspects. An epistemic community is a network of knowledge-based experts who look together at the problems they face, identify various solutions, and assess the outcomes. | Impedovo, 2021 |

| Teachers learning collaboratively with university-based teacher educators | Online learning communities with reflective activities through action research between distant educational environments. | Range of skills. | Helleve, 2010 | |

| Grassroots PLD | Instigated by the teacher rather than a formal organisation that provides access to new knowledge; an opportunity to find and engage with like-minded people, and a safe place to share. | Range of skills. | Holme, Schofield and Lakin, 2020 | |

| Educational Intervision | Problem-solving peer groups providing counselling and mutual developmental support. | Range of skills. | Teachers are helped to find their own solutions and strategies to cope with challenges in practice through systematic experience sharing | Franzenburg, 2019 |