Online learning and teaching: reflections on the case of an online palliative day therapy programme, under COVID-19 lockdown

By Amanda Roberts

Introduction

Introduction

In this thought-piece I share some reflections on online learning and teaching, gained through the design and leadership of an online day therapy programme. In 2018, I left my substantive post in the School of Education, University of Hertfordshire, to pursue a new interest in palliative care. I currently volunteer in the day therapy team of a local hospice. Day therapy offers the opportunity for re-habilitation within the boundaries of patients’ disease (Low et al., 2005). Services offered within day therapy such as occupational therapy, physical therapy, opportunities for the sharing and monitoring of symptoms and activities which offer psycho-social support for those with a terminal diagnosis (Kilonzo et al., 2015) support this re-habilitation. Enhancing quality of life, through focusing on a patient’s individuality and addressing their particular needs, is a central aim of the day therapy service (Hearn and Myers, 2001, in Fisher et al., 2008).

A response to the COVID-19 lockdown

Palliative care patients can suffer what has been termed ‘total pain’ - the physical, mental, social and spiritual pain which can make up the totality of a patient’s suffering at the end of their life (Saunders et al., 1995:45). The concept of total pain reflects the complex nature of care needed to support those with a terminal diagnosis. A recent editorial in The Lancet (2020) argues that a global pandemic such as COVID-19 amplifies such suffering, through physical illness, the exacerbated threat of death, an increase in general levels of fear and anxiety and financial challenges. Alleviation of this suffering clearly needs to be a timely response to the current pandemic.

Unfortunately, the lockdown response to the COVID-19 virus meant the temporary closure of most front-line palliative care day services. In common with many hospices seeking to reduce virus spread (Powell and Silveira, 2020), day therapy provision at the hospice where I volunteer has been suspended. This necessary withdrawal of face-to-face day therapy services is increasing levels of patient distress nationally (Cawley, 2020), as people miss the positive impact on their emotional and physical well-being (Andersson Svidén et al., 2009). This is particularly the case for those ‘shielding’ from the pandemic, that is, remaining in long-term isolation at home and cut off from their established support systems.

Seeking to fill this gap, I am working with a colleague to design and lead an online support programme - BETTER TOGETHER - for patients who were previously attending face-to-face day therapy at our hospice.

The BETTER TOGETHER programme

The BETTER TOGETHER programme allows patients to meet online for conversation, mutual support and shared activities. I host a weekly one-hour session, using the WHEREBY video-conferencing platform, which does not require logins or downloads. This is important as many patients wishing to access the BETTER TOGETHER programme are not technology proficient.

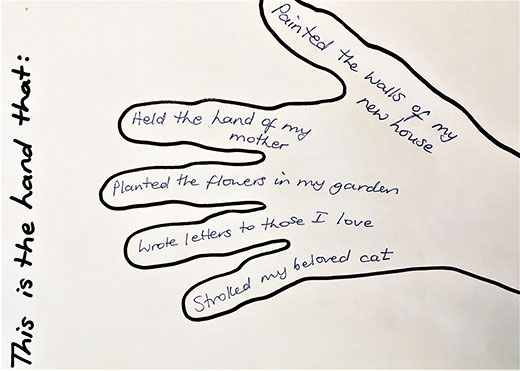

Sessions begin with a catch-up on news, in which I invite each individual to speak. We all take part in seated physical exercise activities, led by a physiotherapist, and I then facilitate an activity. To date, we have enjoyed a quiz and a word association game; we have written a communal poem, with each participant contributing one line, and have pondered on happy memories from the past and hopes for the future, using the stimulus of My unique hand, shown below.

Figure 1: My unique hand – the past

Figure 1: My unique hand – the past

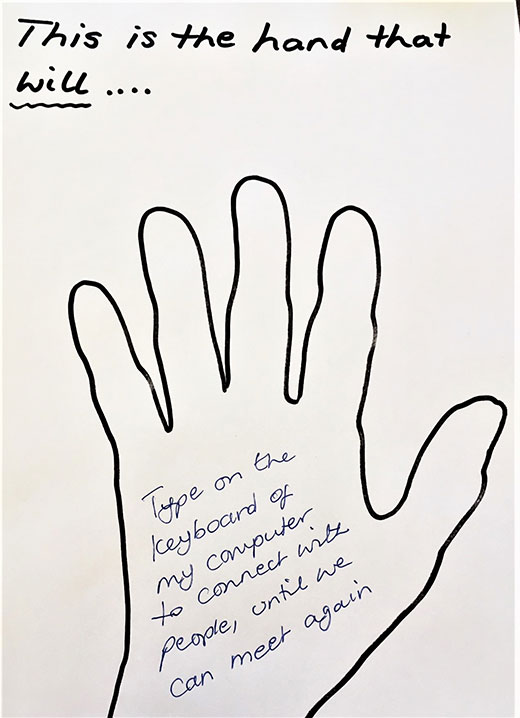

Figure 2: My unique hand – the future

Figure 2: My unique hand – the future

The purpose of this activity, described as by one patient as ‘cathartic’, is to encourage individuals to reflect on the scope and meaning of past achievements, and, in sharing future aspirations, to build a communal sense of hope for the future.

The programme is supported by a website where resources from each session are posted, allowing those unable to join a particular session to remain connected to the community.

Observations about online learning and teaching

So far, this experience highlights some key points about online learning and teaching.

Online learning and teaching can stimulate creative curriculum design

The need to facilitate online learning acts as a catalyst for creative curriculum design. It forces us to re-focus on the aims of a programme and to articulate our approach to fulfilling these aims. A key aim of our day therapy programme, for example, is to empower participants to live well on a day to day basis. We must therefore continue our attempts to design the online programme itself so that the activities are accessible, thought-provoking and supportive for all participants, whatever the challenges of their condition.

Online learning and teaching can enhance learners’ agency

The education element of our face-to-face day therapy service, where a professional gives a lecture each week on an issue such as breathlessness or anxiety, has been replaced by communal sharing of both issues and solutions. Medical professionals are no longer cast as omniscient experts (Foucault, 2003) but instead as group members, undertaking the exercises and commenting on issues raised alongside peers. It is notable that the online nature of the programme tends to break down the unhelpful hierarchy of cared for and carer (Lawton, 2000) and to construct all participants as agential learners.

Online learning and teaching necessitates thinking differently about participant interaction

Face-to-face teaching generally requires groups of learners to come together in one physical space. Learners sit where they choose, at the front, nearer the back, with people they feel comfortable with. They choose to stand out as individuals, being vocal in sessions, or to adopt a listening approach. Such choices are constrained in online sessions.

Although it is possible to use online platforms where only the speaker appears on screen, many facilitators use a ‘gallery view’ option, with all group members constantly visible. Whilst enabling a clear understanding of who is in the room, such options do not allow a group member to ‘sit at the back’. Indeed, in our online sessions I invite each participant to speak. Borne of a democratization agenda, this nevertheless increases patient exposure. We are working with the group to understand and consider individuals’ emotional response to this.

An extension of this issue in online day therapy sessions is the constant presence of the facilitator. The opportunity for patients to talk privately with others ‘in the same boat’, that is, with a terminal diagnosis, is a key feature of face-to-face day therapy. It provides a space where patients can be themselves, sharing their feelings, symptoms and prognosis without considering the sensibilities of family members or friends. We are currently considering appropriate ways to provide this private space in an online environment.

We look forward to continuing to develop our understanding of both online learning, teaching and therapy through conducting an evaluation of the virtual palliative day therapy with our current participants. This will allow us to inform with confidence the debate around the future shape of palliative day therapy services.

References:

Andersson Svidén, G., Fürst, C.J., von Koch, L. and Borrell, L. (2009) ‘Palliative day care – a study of well-being and health-related quality of life’. Palliative Medicine. 23. pp.441–447.

Cawley, L. (2020) ‘Corona virus: How are hospices coping during the pandemic?’ BBC News, 1 April 2020. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-england-essex-52068599 (Accessed: 11.4.20).

Fisher, C., O’Connor. M. and Abel, K. (2008) ‘The role of palliative day care in supporting patients: a therapeutic community space’. International Journal of Palliative Nursing. 14(3). pp.117-125.

Foucault, M. (2003 ed.) The birth of the clinic: an archaeology of medical perception. London: Routledge.

Kilonzo, I., Lucey, M. and Twomey, F. (2015) ‘Implementing outcomes measures within an enhanced palliative day care model’. Journal of pain and symptom management. 50(3). pp.419-23.

Lancet, The (2020) Editorial. ‘Palliative care and the COVID-19 pandemic’, Vol. 395, April 11.

Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/action/showPdf?pii=S0140-6736%2820%2930822-9 (Accessed: 11.4.20).

Lawton, J. (2000) Patients’ experience of palliative care. London: Routledge.

Low, J., Perry, R. and Wilkinson, S. (2005) ‘A qualitative evaluation of the impact of palliative care day services: the experiences of patients, informal carers, day unit managers and volunteer staff’. Palliative Medicine. 19. pp.65-70.

Powell, V.D. and Silveira, M.J. (2020) ‘What should palliative care’s response be to the COVID-19 epidemic?’ Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/ j.jpainsymman.2020.03.013 (Accessed: 11.04.20).

Saunders, C., Baines, M. and Dunlop, R. (1995) Living with dying. A guide to palliative care. Third Edition. Oxford: Oxford University Press.