Overwhelmed by shifting demands of commissioned research

At a recent event, I mentioned an interaction from several years ago: when conducting a tricky piece of commissioned research, a civil servant had asked me, “have we made you cry yet?” This piece is my reflection on that interaction.

I cried when I was in pain. I cried when I felt joy. I cried when the laughter wouldn’t stop. I cried at feeling futile. I cried when I failed others. I cried at feeling failed by others. I cried at failing myself. I cried because I’m human. I cried because I care.

But I didn’t know how to respond when the data analyst asked:

“Have we made you cry yet?”

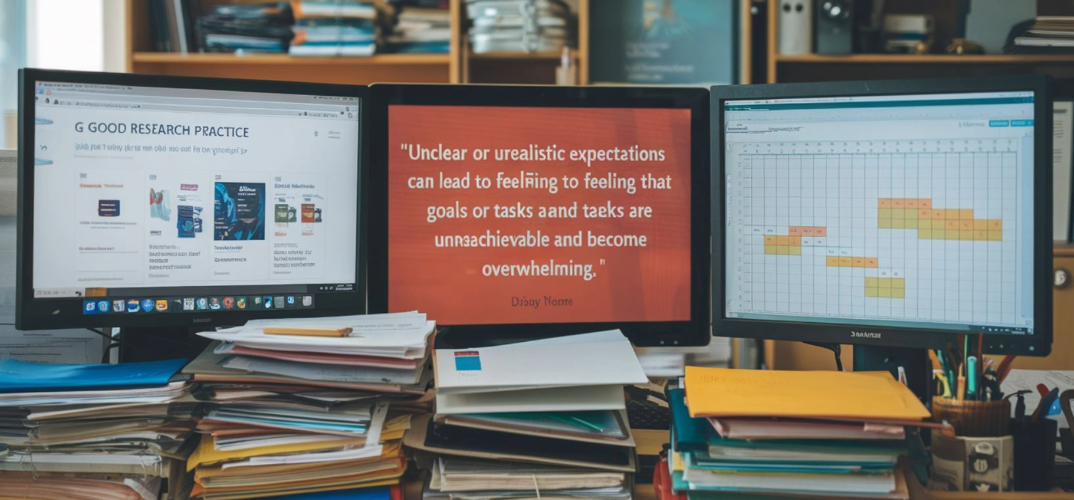

Embedded in that question was the acknowledgement that my team and I had been working exceptionally long days, to ever-changing requests. We had a contract, we had fortnightly touchpoints, we had a deadline to make and a publication to produce. We knew how to work accountably, transparently and rigorously. We knew what had been commissioned so we thought that we knew what was wanted. Then, the requests changed. During the short life of the contract, political priorities shifted and although we had been working to shared understanding, the requirement itself developed. It didn’t shift all at once, it evolved through redefined parameters and a subtly growing demand for things that hadn’t been contracted. This was often couched in quality assurance terms, even when requests related to substantively different tasks than those which had been agreed.

Could we have refused to deliver?

Possibly, but it would have been reputationally risky for all concerned. At the time, I don’t think it ever entered my mind that that would have been an option. None of this was ever acknowledged with a variation in contract. It was never really acknowledged at all. Not until that relatively junior member of the commissioning organisation asked: “have we made you cry yet?” That person had been working 14-hour days, six days a week. They had been forced to change their requests to us and expectations of us. For them, this was a fairly standard operating process. They were a hard-working, diligent civil servant who did their job well. They were being asked to do more than it was possible to do within their contracted hours. That was what was being passed down to us.

In academia, that’s also fairly normative. When I ran my first research project, there were sofas in offices; research students and junior staff sometimes found it more sensible to sleep on those sofas than walk the 20 minutes home. That walk each way, was a waste of time that we didn’t have. We showered in the gym and ate from vending machines, convincing ourselves that if we at least chose milk and fruit, it was vaguely healthy. I would be horrified if any of my students worked similar hours on their research - particularly as so many of them have to work to pay for fees and living costs that are way higher than any loans/grants they can obtain. Too many students are already stretched unsustainably.

As I started to lead research, then became principal investigator of larger teams, I always took on more to try to protect others, while still delivering on time and within budget. This always meant working for more time than we had been contracted, frequently undertaking very long days and weeks in order to meet the calendar deadline. So, whose time and budget was it actually within?

Now, all these years later, ME has finally forced me to acknowledge my own frailty and fatigue and I have learnt how to better manage my time. Now, finally, I say no to work that can’t be delivered, that will require more than is being acknowledged to do properly. I flag limitations of what is possible and try to set meaningful expectations all round. Yet, I still work on nonworking days, I’m paid to work fractionally and do take time off but when work is due and a deadline needs to be met, my hands will be on deck.

Have they made me cry?

Probably, sometimes. But never in defeat, never without hope. On dark days, it’s possible to despair of the situation of higher education in this country, for research, progress and student futures. Then, a paper gets accepted, a meaningful bit of work looks exciting to embark upon and a student blindsides me with their insight, enthusiasm and compassion. I cry because I’m human, I cry because I care.

Author

APRG lead and Professor of Forensic Psychology, Joanna R Adler